The Integral Breath

To breathe is to live. To breathe deeply and fully, and into the core, provides the potential to live deeply and fully. The fundamental act of inspiration and expiration is one of the great miracles of existence. To inhale deeply is to fill us with the energies of life, to be inspired. To exhale fully is to empty ourselves to the unknown, to expire. For thousands of years, breathing awareness has been an integral part of meditation, an integral part of the journey toward our own essence. Attending to our breath attracts our awareness to the inner depth that is the extraordinary temple of our body. Here, it awakens our inner dimension of silence.

Integral is defined as “necessary to the whole, essential for completion.” In the Integral Breath, the first impulse arises from the diaphragm. In deep, relaxed breathing, the diaphragm controls the process. The diaphragm is an inverted U-shaped muscle located at the base of the sternum. The top of the inverted U pulls gently down on inhalation, as it pulls air deep into the lungs. It releases on the exhalation, moving air out. Although the muscles between the ribs expand as we inhale, the breath does not originate from the rib cage. The chest and ribs expand as a result of the bottom of the lungs filling. Your abdomen softens to allow your diaphragm to be active. You will feel the abdomen swell slightly, in the area above the navel.

A deep breath and a full breath are not the same. A deep breath comfortably expands the bottom chambers of the lungs. A full breath expands the lungs to their maximum capacity. In a state of deep relaxation, you breathe deeply, but breathing is barely visible, and therefore not very full.

The Breathing Practice

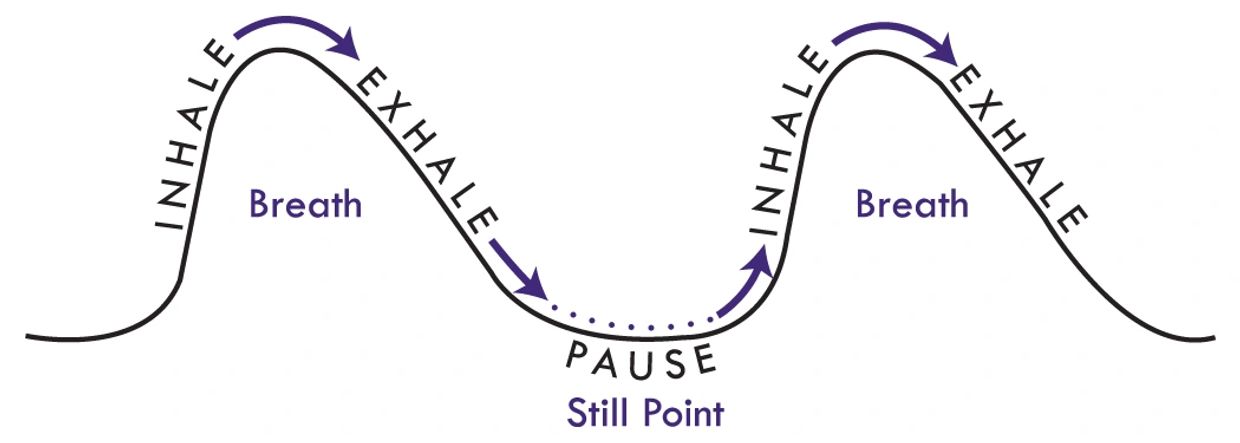

Practice the Integral Breath anywhere; sitting, standing or lying down. In the beginning, it is easier to access the correct muscles while lying down. Adjust your spine to its fullest length. Inhale through the nose. Feel the ribs as they swing apart from each other. Fill the lungs to just below your collarbone, so that the muscles surrounding neck and collarbone stay at rest. Inhale over the top of the breath and allow it to slide directly into the exhalation, moving in a continuous flow. Now let the breath come to a standstill, wait….for the impulse for breath to rise

again.

Exhaling is effortless, nothing happens--you just let go until your breath comes to rest, and then wait. Wait--while the bronchi exchange their gases. Wait–until the neurological impulse stimulates the brain for the next breath. When the gas exchange is complete, an impulse will be sent to the diaphragm to repeat the cycle. The wait--known as the Still Point--might be as brief as one second or as long as five seconds. Each breath may be a little different. Direct your attention to the Still Point between breaths, not controlling it, just attending to it.

If you have difficulty breathing IN through your nose, try making a slight purse to your lips, very soft, and SIP your breath in through your mouth, almost like you are sipping through a large straw. Again notice the ribs expanding and falling away with each breath.

Continue with the Integral Breath as long as you are comfortable. If your breathing starts to feel fatigued, breathe comfortably without judging or controlling the breath. When you feel comfortable again, resume the Integral Breath practice. Start with five minutes or less, build up to ten minutes. Twenty minutes would be a long and disciplined meditation.

After regular practice, you will be able to regulate your parasympathetic nervous system response, the relaxation response, with only three Integral Breaths, accessing the regenerative powers of relaxation almost instantly.

The Integrated Breath Cycle:

Assume a long spine position Inhale through the nose or a soft purse to the lips–the active phase of breathing Pull the diaphragm down–expanding the lower ribs Fill the lungs from the bottom upward to just above the nipple area Slide directly into the exhale–the passive phase of breathing Release the breath effortlessly Exhale until the breath stops on its own–focus on the Still Point Wait for the brain to signal the diaphragm to resume its new breath cycle

Incorrect breathing has several adverse affects on the body. There are two common incorrect breathing patterns. First is when the breath is held after inhaling. Breath-holding causes an incomplete exchange of gases, causing the blood to acidify. Acidified blood is associated with inflammatory processes in the body. The second pattern is called thoracic breathing; the way we breathe during the stress response--short breaths, high in the chest, using the neck muscles instead of the diaphragm. Thoracic breathing engages the stress response of the nervous system, activating an on-going stress response. As adrenaline is dripped into the body, there are hundreds of biochemical, hormonal, and glandular changes that occur, leading to stress exhaustion.

Tips:

- As a beginner, exhaling through your mouth helps your lungs to empty more completely. You can only breathe in as much air as you breathe out. Allow your jaw to hang loose. Your tongue flattens at the back of the throat with the exhale. It rises slightly as you inhale. This helps alternate between your nostril inhalation and mouth exhalation.

- It helps to think of your breathing as a bellows, with the tip pointing up. Imagine your diaphragm as the handles of the bellows pulling your ribcage open, drawing air in. Feel the exhale and inhale flow through the back of the throat. A soft throat and neck will allow clear and open passage of air. Try making a soft whispered “Haah” sound on the exhalation with no tension in the lips.

- If you have any difficulty, be sure to try the sipping breath with softly pursed lips. It is most effective in getting the ribs and diaphragm to work together.

- During exercise, the body inhales whenever it expands and exhales when it contracts. In other words, as the front of your body opens, you inhale; as the front of your body closes, you exhale. This is especially true during Yoga postures and in stretching, but not, during strengthening.

- If you have an incorrect breathing pattern and desire to change it, place some bright stickers around your environment (on your review mirror, on a clock face, a light switch, etc.) to catch your attention and trigger your Integral Breath.